SITE VISIT: La Perle, the story behind a show like no other

How MEP engineering keeps the magic sparkling night after night

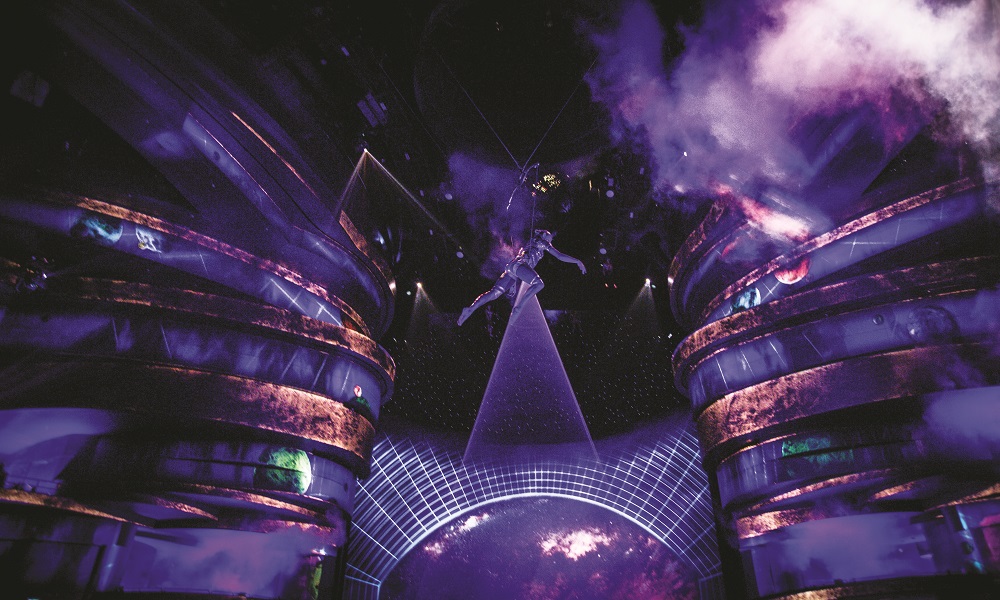

Almost exactly a year ago, the doors of a show like no other in Dubai opened for the first time, welcoming visitors to a spectacle previously only seen in cities like Las Vegas and Macau. Designed to be a permanent feature of Dubai’s entertainment landscape, the launch of La Perle by Dragone introduced both residents and tourists in the city to a water-based show that combines gravity-defying acrobatics with spectacular water and special effects to tell a fantastical story.

Developed as part of the entertainment options at Al Habtoor City, the show opened in September 2017 and is housed within the V Hotel, a 356-room hotel that is part of the massive hospitality complex alongside Sheikh Zayed Road. Created by Dragone Studios, a Belgian creative company that specialises in large-scale theatre shows, the theatrics and stunts have been built around a theme that reflects Dubai’s cultural heritage, its producers say.

Envisioned by Franco Dragone, the founder of the company and a former director of several of Cirque du Soleil’s most famous shows, La Perle takes place five days a week, with two shows a day at a custom-built theatre that houses 1,300 people.

While the show itself is visually spectacular and a remarkable combination of talent, athleticism, precision timing and close coordination, the true magic lies in the design, building and operation of the venue itself. Big Project ME was recently invited for a behind-the-scenes tour that reveals the mysteries of the show and highlights how technology and engineering have been used to create a platform for the story to unfold.

The starting point is the theatre itself, built around the specific needs of the show. The building is a G+6 structure with four basement levels. It houses a reception area, the theatre and VIP lounges in the public access areas. There are also dressing rooms, a gym and physiotherapy facilities for the actors.

Offices and workshops for the production staff are also housed within the structure, while the basement levels hold the show’s heart, with a high-tech pumping system that allows the core element – water – to be rapidly moved onto and off the main stage.

Essential to this process are two 600hp pumps that move water at different pressures to fill up the stage. Capable of operating at 1,000l/min, the pumps fit the requirements of the special effects team and are part of a network of pipes and tanks that can simulate waterfalls and thunderstorms while also rapidly filling the stage to up to 20cm.

In order to achieve the results they were looking for, Julien Zazzaretta, technical director at La Perle, says that coordination between the team from Dragone and the construction stakeholders was essential to the success of the project.

“Most of the time, we design shows that fit the region, and here we have the story of a pearl, which fits the region but is loose enough to be built around everything. It’s something that you identify with this region, and it fits with the architecture of Dubai. The show’s theme is one that represents technology, which is also something that Dubai always wants to present to the world,” he says.

“So what Dragone did was to hire a theatre consultant who took care of the construction side and monitored the site coordination. On the production side, we came in to verify things as we know what the specifications are, and we worked with the theatre consultant and the vendor (Al Habtoor City) to ensure that we had something we could use.

“Obviously, we had to voice our opinions or raise the alarm when it comes to final approvals or system acceptance. We clearly stated that we would need a particular volume of water in a particular number of seconds. If that wasn’t achieved, we would have needed to make a decision about whether we had time to change it, or if we could accept it for the show.

“Of course, delays sometimes happen, and we did have some delays, because it’s precision work. We had a huge timeframe for all of this. Phase two of construction was what we called ‘dust-free’, meaning that there was no concrete works ongoing. This took about three years, and then there was another year of moving the show in.”

HLG Contracting was appointed as the main contractor for the project, he adds, pointing out that it was responsible for subcontracting various facets of the project. To that end, it appointed Commodore Contracting for the MEP works, while Al Rawda Building Contracting was appointed for drywall and painting and Butler Engineering was contracted to oversee fire and safety works.

Khatib and Alami, a local architecture firm, was appointed to work on the design of the theatre, partnering closely with Dragone Studios and Al Habtoor Group to deliver the look and feel of the project. Assisting was theatre design consultancy Auerbach Pollock Friedlander and acoustician Jaffe Holden.

“It started with the concrete pouring really, it’s very specific work,” Zazzaretta says. “The pool has to be very specific, the piping systems have to be exact, and then you go from there and build the room. We had this huge challenge to build the dome [within the theatre], as every panel is a custom shape. They needed to have a tolerance of within 2mm, as that was the specification.

“The room itself is pretty huge, it’s just been narrowed down to give the feeling of a cave and it then opens up because it’s very high. The audience enters through the atrium and then walks through an area with a low ceiling, and then it just opens up. For us, while this is a medium-sized theatre – there are much bigger capacity ones out there – the height is always the same [no matter the theatre]. We need the height for effect.

“It’s almost like being in a cathedral, you always look up to the ceiling. That’s what keeps the audience interested. We purposely don’t want to hide too much, because people want to look up and see something and think, ‘That’ll come later in the show.’ Other shows try to hide everything, but we did the opposite.”

A key element of the show is the use of artificial fog and water sprays, which means temperature control plays an important part, he adds. As a result, a state-of-the-art BMS system that can manage and adjust the theatre’s HVAC systems is vital to the success of the show.

“For us, it’s very important to have good control over the HVAC and the dehumidifier. The audience does need to stay cool, but the performers also need to stay warm. We fought a lot in the beginning to have that balance.

“Also, during the show we have smoke effects and we manipulate the draught. If we were just to blast air into the air and make it cool, the fog wouldn’t last a second. It would just go into the audience or wherever it wants to go, even outside if there’s a door open! As a result, we try to balance the room so that whenever we put fog on the stage – and it’s a challenge every show – we can keep it for however long it can be on stage.”

All of this, along with the water and lighting effects for the show, is managed from a control room high above the stage floor. From the panels in this room, operators can manage the entire show, Zazzaretta explains.

“The operator here controls all the water effects, and for the show has presets in place to switch the HVAC systems on and off. We have three automation operators in the control room; we also have a lighting operator for the moving lights, and we have a video operator just for the projections. We also have a special effects operator as well. Everything is cued by the stage manager, who looks at the stage and gives cues according to various situations, whether it’s for the music or for the actors.”

The most crucial element of the entire production is the pool at the centre of the stage, around which the entire show is built. Fed through an intricate network of pumps, tanks and pipes, the pool is part of a larger underground network that holds 2.7m litres of water.

Performers are able to dive into the pool during their acts, and are also able to navigate their way through a series of underwater tunnels into the backstage areas, allowing costume changes and changeovers without interrupting the experience for the audience.

“The pool is five metres deep in the performance area, but we have other areas that go up to 12m deep. This means that there is potential for future expansions to the show. We could have a stage lift and bigger props if we desire – we’ve left our options open. This is a show that can run for 10 years, so at some point they’re going to want to invest money and make it interesting for audiences again. There’s a bit of headroom there for decisions to be made.”

This pool system also feeds into other elements of the show, with Zazzaretta explaining that a quick-fill tank high up in the rafters of the hall is used to fill the stage with water at a high velocity. For other effects such as rain, cascades and waterfalls, a piping system connected to the pool is used.

“What happens during the show is that we fill the quick-fill tank, which is above the stage, and then open four valves on a 600mm pipe, and gravity does the rest as water fills the stage. The quick-fill tank holds about 150m3 of water, which is enough to fill the stage. The pumps fill the quick-fill tank and then we drain it into the basin, which is the stage.

“We never really lose water – any loss is minimal. We recycle the water and the only time we actually lose water is when we backwash the system and clean the sand filters. But other than that, we try not to lose too many litres. This is because we were allowed to build this theatre in conjunction with not wasting water. We’re not throwing it away, we filter it and keep it.”

One of the most interesting aspects of the construction of the stage is using the floor as a drainage system, he points out during the tour.

“During the show, everything is wet, people are coming in and out of the pool, so we have the same surface all the way through. It’s a track and field type surface that’s still got a grip when it’s wet. The only difference is that we have laser cut holes into the material so that water can drip out, allowing the entire floor to work as a drainage system. But if you step on it, it still has grip.”

Known as Chemgrate, the material is a type of fibreglass-resin that is extremely strong and resistant to the chlorine in the water. However, Zazzaretta says the production staff make sure to disinfect it regularly, so as to protect the performers’ health.

Given the amount of water used in the show, protecting the performers’ well-being is another important aspect, with stringent procedures and systems in place to maintain water quality and level.

“There are filtration pumps and there’s a water management system. It’s similar to a swimming pool, but much more upscale. We add water bubbles to the surface of the water for two reasons – one is to hide people, and secondly to soften the water for the performers when they enter it.

“There is also an auto-dosing system for the pool that happens four times a day. It’s important for us to keep the water quality to a very high standard, because we have performers in the water. If they even get an ear infection it could complicate things, as they could lose their sense of balance and they wouldn’t be able to perform.”

However, these measures also have a downside as the chlorinated water presents the production team with a challenge to maintain and preserve equipment, he says.

“There’s a lot of corrosion protection and a lot of dehumidifying going on. We have winches, disc-brakes and other equipment that needs to be maintained, most of the time in water and steam – everything that is meant to corrode metal! The perfect conditions to have metal corrode is chlorinated water at 32 degrees Celsius, and that’s what we have! Even stainless steel corrodes in these conditions.”

This presents an interesting challenge for the engineers and the production team, he says, as not only does the finale of the show include a giant metal globe descending from the ceiling, containing five motorbike stunt drivers performing death-defying feats, but throughout the show performers use winches in the ceiling to perform acrobatics at dizzying speeds and heights.

“Nothing is hydraulic in the show,” he asserts. “We tried to go away from using hydraulics because of the water elements. It’s a huge challenge to separate hydraulic technology from the performance spaces where people are going in and out of the water.

“What we do is have winches that bring the globe down and we put anchors on it and then use tension against it. Twenty tonnes of force pull against the globe, so as to compensate for the five bikes generating G-force inside it. We then have a separate winch which constantly holds the bottom third of the globe, so that whenever we want to split it, we’re still holding tension against it,” he explains.

The safety of the performers was taken into consideration right from the beginning of the construction design process, Zazzaretta adds. He reveals that the show’s engineers and the building’s engineers worked together to over-engineer the safety systems, to ensure no risks were taken with the performers’ lives.

“We have 60 winches up in the ceiling that can run at four metres per second. If for some reason we load these winches to the max capacity and run all of them at the same time, and then the power goes out, the force that will be created is a potential risk for the whole steel structure of the building.

“This is the worst-case scenario, of course, as we would never do this in the show, but the building has still been designed for this capacity. It’s a massive steel structure that can support four times the size of this show,” he concludes.